Netflix calls it "ordinary course of business." The data tells a different story about who wins, who loses, and why advertisers should be paying closer attention than anyone.

On Friday, after the closing bell, the Wall Street Journal reported that the Department of Justice launched an antitrust review of Netflix's $82.7 billion bid for Warner Bros. Discovery. As part of the probe, the DOJ issued a civil subpoena to another entertainment company asking it to describe "any exclusionary conduct on the part of Netflix that would reasonably appear capable of entrenching market or monopoly power."

Netflix's Chief Global Affairs Officer, Clete Willems, went on Fox Business and called it routine. "This is ordinary course of business," he said. "The Department of Justice is going to investigate this transaction and make sure it's good for our economy and consumers."

Perhaps. But there's nothing ordinary about what this deal would do to the streaming landscape. And the conversation happening in Washington is missing the point that matters most to anyone buying or selling Streaming TV advertising.

"Last year was the year of consolidation," said Jean Carucci, best known as "The Streaming Strategy Scholar" and Principal of Carucci Consultants, a streaming advertising veteran who has worked on the agency, pay TV, and network sides of the business. "This year is the beginning of the mega mergers." Jean joined the State of Streaming for a live breakdown of what both potential WBD deals mean for media buyers, and her analysis paints a picture the Senate hearing never touched.

What The Senate Hearing Missed

The Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust heard testimony last Tuesday, and the questions were predictable. Senator Mike Lee of Utah warned Netflix could become "the one platform to rule them all." Senator Josh Hawley pressed for commitments on union labor and a 45-day theatrical release window for Warner Bros. films. Netflix committed to both under oath.

Pricing came up. Netflix pointed out that its cost per hour of content is roughly 36 cents compared to Paramount's 70-plus cents. They promised more content for less money and a discounted bundle for the 80% of Netflix subscribers who also subscribe to HBO Max.

All of this makes for good television. But none of it addresses the structural question that actually matters for a sustainable streaming advertising ecosystem and since ads are what pay the bills, it's worth mentioning.

The Question Washington Isn't Asking

Here's what the Senate hearing didn't touch: what happens to the advertising inventory landscape when one company controls Netflix's audience scale and WBD's content library?

Netflix made its pitch in consumer terms. More content, lower prices, theatrical distribution, jobs in all 50 states. But the advertising implications of this deal are enormous and almost entirely absent from the public conversation.

Carucci framed it bluntly. A combined Netflix and WBD would offer "limited premium inventory. Premium, no doubt. Each one of these companies has an ultra light ad load, four to six minutes. That will severely limit the number of ad slots available." High demand, scarce supply. "I can assure you those will be very high CPMs."

And the data transparency problem makes it worse. "Let's remember that Netflix has never really published subscriber numbers," Carucci said. "They've traditionally relied on monthly active viewers. And that actually just inflates the household reach number." Warner Bros. Discovery's Max averages between eight and ten million ad-supported subscribers. Combined, the audience is real but the visibility into it remains, in Jean's word, "murky."

For buyers used to planning with precision, that's a problem. You're being asked to pay premium prices into an environment where the inventory is limited, the audience measurement is opaque, and the ad load gives you almost no room to optimize.

The Data Behind the Power Shift

This is where it helps to look at what Reelgood CEO David Sanderson told the State of Streaming podcast recently, because his data quantifies exactly what's at stake.

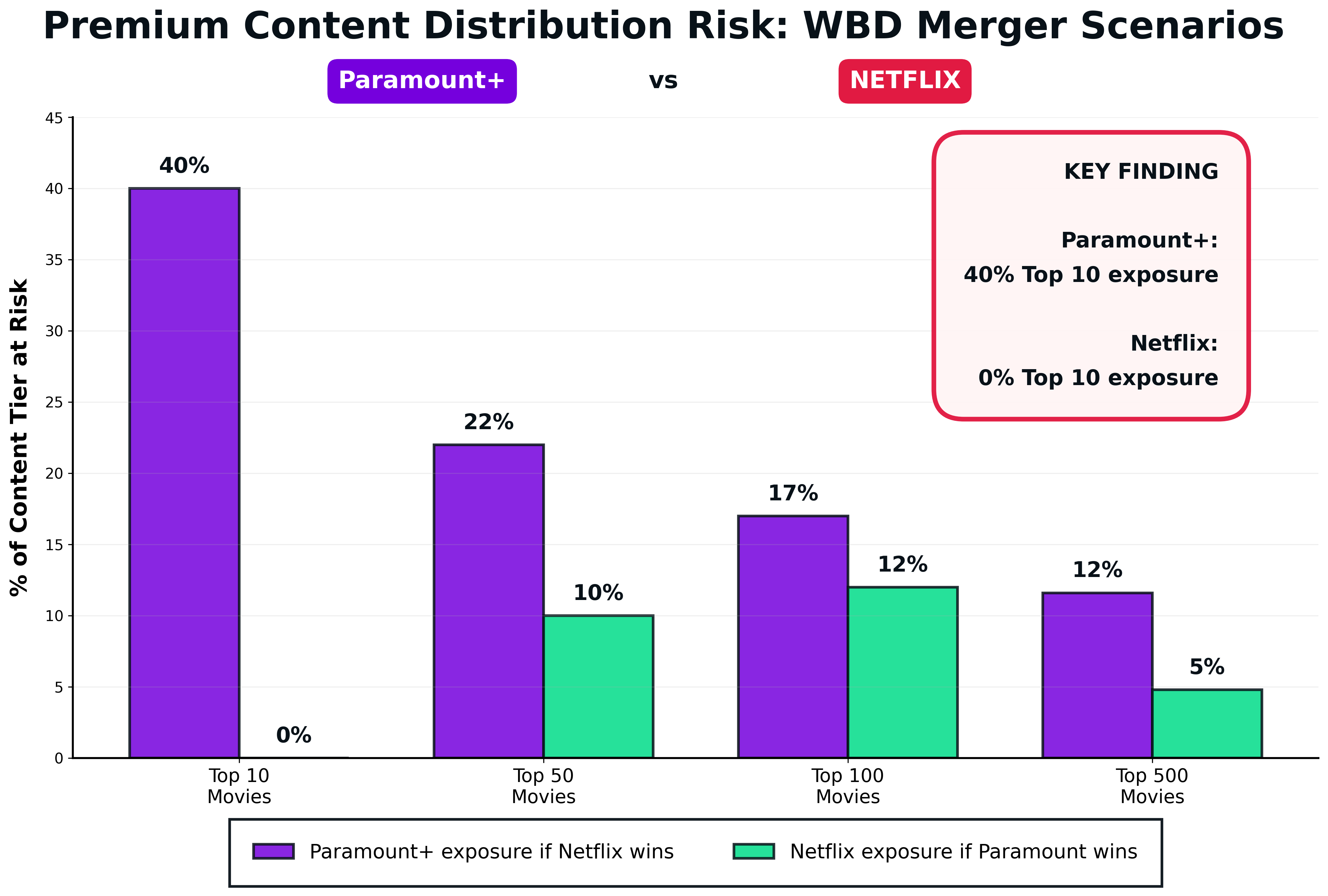

"When we looked at the top 10 titles on Paramount, 40% of them are licensed from Warner Brothers," Sanderson said. "When you compare that to Netflix, none of the top 10 are licensed by Warner Brothers."

Zoom out to Paramount's top 50, and a quarter of their highest-performing content comes from WBD's library.

"For Netflix, buying Warner Brothers is really an offensive move," Sanderson said. "For Paramount, it's a defensive move."

Netflix's global affairs officer made a version of this argument on Fox Business, though he framed it differently: "Right now we do not have 100 years of iconic IP, shows like Harry Potter or Sopranos. We don't have theatrical distribution or the world-class studio that Warner Bros. has. We are going to bring these things together and give consumers more content for less."

That's the consumer pitch. The business reality is more pointed. Netflix doesn't need WBD's content to survive. Their top 10 has zero WBD titles. They want it to dominate. Paramount, on the other hand, loses a quarter of its best-performing catalog if Netflix acquires WBD and pulls those licenses. That's not competition. That's a structural collapse of a competitor's content supply chain.

Netflix acknowledged as much indirectly during the hearing, noting that Paramount's competing bid involves "$6 billion in synergies, which is code for $6 billion in job cuts." Netflix positioned their own cost savings as "primarily from licensing savings." Read that again - licensing savings. That means pulling content back from competitors and keeping it in-house. Exactly what Sanderson's data predicts.

Two Deals, Two Completely Different Ad Environments

Jean Carucci broke down the contrast in terms every media buyer can act on immediately.

A Netflix/WBD combination gives you premium drama and film access with prestige content environments. But the practical reality is "low frequency of events," he said. "Those prestigious dramas don't have a deep library or twenty-two episodes. They're much less." The ability to advertise in award-winning content is real. The ability to build scale, frequency, and endemic relevancy against it is limited. "It's great for luxury and high-end brands seeking prestige. It's just not going to work if you're a mass market company looking for scale."

A Paramount/WBD combination offers something fundamentally different: endemic lifestyle content, reality programming, and live sports. "Food, home, eating, competition," Carucci says. "Advertiser relevancy is very, very high there." The combined live sports portfolio alone (March Madness, NFL, NHL) would create what Jean calls "a fierce competitor to the juggernaut of Disney's ESPN." And the integration opportunities are cheaper, faster to produce, and available in far greater volume. "You can own a show. You can own the first pod. So many different opportunities."

The distinction matters because it changes how you plan. Netflix/WBD is a prestige play with limited inventory and premium pricing. Paramount/WBD is a scale play with endemic content and integration depth. Both have value. But they serve fundamentally different advertisers with fundamentally different objectives, and right now the public conversation treats them as interchangeable bidders for the same asset.

The 45-Day Window and What It Means for Streaming Ad Inventory

One detail from the hearing that flew under the radar: Netflix committed under oath to a 45-day theatrical release window for major Warner Bros. films. That means every WBD theatrical release would hit Netflix's streaming platform (and its ad-supported tier) roughly six weeks after its theatrical debut.

For advertisers, this creates a predictable, premium content pipeline feeding directly into Netflix's ad inventory. Every major Warner Bros. release becomes a tentpole advertising moment on Netflix's platform six weeks later. That's a structural advantage no other streaming ad platform can currently promise.

Carucci's advice here? It's direct: "Lock in those high-affinity tentpoles or events before the price resets in the marketplace. Premium inventory is going to become competitive very, very quickly. Try to commit early so you can get the best value."

What Buyers Should Be Doing Right Now

The DOJ review means this deal isn't closing tomorrow. But the strategic implications are already in motion. Content licensing negotiations are happening now. Platform strategies are being set now. Upfront conversations are happening now.

That's why we asked Jean Carucci, The Streaming Strategy Scholar to outline five questions every media buyer should be asking their streaming partners heading into this upfront season:

Can I activate my own first-party data on your platform, or am I relying solely on your native targeting tools? "As ownership shifts, you need to safeguard your targeting consistency," Jean said. "You need to make sure that your data portability is protected." This isn't a theoretical concern. When platforms merge, data systems merge, and the targeting infrastructure you built your campaign on may not survive the transition.

What is the actual ad-available subscriber base and impression supply? Not monthly active viewers. Not inflated household reach. The real number of people you can actually serve an ad to, with the transparency to verify it.

What content am I actually buying against? Sanderson's data already shows the vulnerability. Forty percent of Paramount's top 10. A quarter of their top 50. All from WBD. If Netflix pulls that content post-acquisition, the platform you're buying today might not have the same content environment six months from now.

Does your ad tech stack support interactive, shoppable, and outcome-driven formats? "A thirty-second ad just to increase brand awareness is done," Carucci said. "This has got to work harder." If the newly merged entity can't support the formats that drive measurable outcomes, the premium you're paying for prestige content isn't translating into performance.

How can my brand be on the home screen during the transition? This is The Streaming Strategy Scholar sleeper pick. "That home screen is the most valuable piece of real estate in streaming," he said. When a merged platform launches a new interface, millions of subscribers are rediscovering what's available. "If your brand can be there at that moment of selection, that's a win-win."

The Bigger Picture

Here's what ties all of this together. The streaming industry just completed what Carucci calls "the plethora of 'Plus' era" and is now deep into mega-merger territory. The number of places to buy advertising is about to shrink, again. The complexity of buying it is about to increase, again. And the leverage advertisers have is about to shift in ways that most media plans haven't accounted for.

"We've sort of just traded off subscribers," Jean said. "There's only so many people who are going to subscribe to so many streams. There's got to be a point of diminishing returns. And now how do I keep those subscribers? Therein lies the challenge. That's why we're in this state."

For sellers competing with Netflix, the window to differentiate is right now, before the deal closes, before the content library consolidates, before the ad dollars follow the eyeballs to wherever the best content lands.

And if you're Netflix, the playbook is clear. They said it themselves on national television: more content, less money, theatrical distribution, and licensing savings. Every one of those moves consolidates power. Every one of them reshapes the advertising landscape. The only question is whether the DOJ decides that's a feature or a problem.

Listen to Reelgood CEO David Sanderson on the State of Streaming podcast and Jean Carucci, The Streaming Strategy Scholar on the State of Streaming LinkedIn Live Stream for the full conversations behind this analysis.

.png)